Dr. Kathryn Fentress

Letter to the Editor of the Daytona Beach News Journal, June 15, 1964:

“I live in Ormond Beach, but I write from the county jail in St. Augustine. I write to you, my community, because I learned that you have been informed of my presence here and I wish to discuss it with you. Twenty years ago this week my father was killed in action on an island in the Pacific, fighting for the freedom of his family, his country, his world. Twenty years ago, on the same day he died, I was born, and it is fitting that I am now fighting for the same thing.

The army I have joined is a non-violent one born out of suffering and love and concerned not only with the welfare of America’s Negro citizens but with the spiritual well being of our whole country. I marched quietly with more than 400 others through the streets of St. Augustine and looked into eyes of hatred. I felt sick to my stomach when some behind me were attacked and all we knew was the sound of screaming, bricks being thrown, and barking dogs.

I hurt for those that suffered then, I hurt because there is only one of me from my community; I hurt for my state that tries in vain to cling to the immoral traditions of the past; I hurt for my country that has failed to live up to the principles on which it was founded. I hurt for all humanity that has not yet learned how to live in a spirit of love and brotherhood. That is why I am here: I hurt.”

Kathryn Fentress was 17 years old when she was sent to a Conference on Human Relations, held in Nashville, Tennessee by her Congregational Church in Daytona Beach. Florida. It was the summer of 1961. She was a white young woman, born and brought up in the south, between her junior and senior years of high school, an honor student, planning on college in another year. Her sights were set on Duke University. Nothing in her life before that conference could have predicted that she would write that letter from a St. Augustine jail 3 years later. But nothing was the same for her after that conference.

Kathryn Fentress was 17 years old when she was sent to a Conference on Human Relations, held in Nashville, Tennessee by her Congregational Church in Daytona Beach. Florida. It was the summer of 1961. She was a white young woman, born and brought up in the south, between her junior and senior years of high school, an honor student, planning on college in another year. Her sights were set on Duke University. Nothing in her life before that conference could have predicted that she would write that letter from a St. Augustine jail 3 years later. But nothing was the same for her after that conference.

It was there that she met a group of young people, led by John Lewis of Georgia, a sharecroppers son, a student at Fisk University where the conference was being held, and who would, one day, be a future United States Representative from the state of Georgia. He was organizing a number of students to do some picketing there in Nashville, protesting against the segregation laws and for the civil rights of all Americans. He was a powerful speaker, as were others, and the young people at the conference were ready to listen, debate and take action. What they had to say about civil disobedience, doing what they could to right the wrongs of the segregation laws resonated with Kathryn and she joined a group that picketed Morison’s Cafeteria. She returned home, inspired by the enthusiasm of the young people she had just been with and the idea that there was actually something she could do to help right the terrible wrong she saw around her. She reported to the panel of elders of the church that had sent her, enthusiastically urging them to take action in the cause of civil rights, in the name of Jesus’ message of brotherhood and love and tolerance.

Kathy says, “I saw Jesus as a model of social activism. The Elders could not have disagreed more. They listened, said thank you for your report and shelved it, never to be seen again. I lost my trust in them, feeling they were hypocritical. I was heartbroken and stopped going to church. Something deep inside of me had been moved at that conference. I believe there are moments in our lives when we are deeply touched by something and that we cannot avoid the call. Something had gone down into the soul of me. I knew, without a doubt that I needed to stand up and participate in some way.”

Kathryn finished her senior year and began her studies at Duke University. In the summer of 1963, she was visiting some friends – students at Bethune-Cookman College in Daytona Beach, an historically black college near Ormond Beach. They began talking about the protest actions underway that summer in St. Augustine. They spoke about a young dentist there who was organizing young people in protest demonstrations.

Kathryn urged her friends to go with her to St. Augustine, and join the group of protestors. They drove up, not knowing anyone, but soon found the contacts they needed. A sit-in at Woolworth’s Dime Store on King Street was being planned and Kathryn and her friends joined it. Some black kids went in to sit at the counter and request service, which was denied, of course. The rest of the young people, black and white, marched in front of the store with protest signs. She drove up to St. Augustine several times that summer to join in other actions, going home each evening. She joined the Bethune Cookman students on a bus to Washington, D.C. to take part in the March on Washington that summer, and to hear Dr. Martin Luther King give his ‘I have a Dream Speech.’ She could not have imagined as she listened to him that she would be personally involved with him the next summer.

Back in school at Duke, in the fall of 1963, Kathryn became involved with some of the activist students there. They were doing voter registration drives in eastern North Carolina, as well as some sit-ins and a march from Durham to Chapel Hill. She was arrested at Chapel Hill and went to jail. One of the motivating factors for her that year at Duke was Harry Boyte. His father was Harry Boyte, Jr. who was the only white man who was part of Dr. King’s council – the upper echelon strategizing group. His son, her friend, Harry, was in close communication with his father and kept the Duke protest contingent informed of all the actions that Dr. King’s organization, the Southern Christian Leadership Council (SCLC) was doing and of their hopes and plans. That spring, there was a steady stream of students, ministers, and other concerned people from the north coming down to St. Augustine to demonstrate.

“I joined them in June of 1964,” Kathryn writes. “Two days after my arrival, Dr. King and Reverend Ralph Abernathy arrived, joining Reverend Andrew Young, who had been in town already.. In the evenings, I joined the many other protesters – both local and outsiders – in the black churches, usually a different one every night to hide from the white shooters. During the day, we trained in the tactics of nonviolence. We practiced being quiet when attacked verbally, going limp when arrested by the police, and shielding our bodies and heads if attacked with clubs. We organized meals for the workers and planned strategies.

Finally came the night Dr. King came to speak to us. Although the room is packed and very warm, his is the only voice that is heard. He tells us of the philosophy of non-violence, he inspires us to believe in the hope and power in us to stand up for what we believe. He challenges our minds; he lifts our spirits, and then he speaks to our hearts. I hear deep sadness in his voice for the injustice in our country. His kindness moves us to tears. Then comes the most powerful message of all. He tells us, ‘I am going to ask you to march for freedom. I am going to ask you to go out into the night and March, I am asking you to face hatred and possibly even violence from the people in this community – but I don’t want you to go unless you have love in your heart. I don’t want you to go unless you can look those Klansmen, those police, those angry people in the face and know them to be your brothers and sisters. If you can’t go with love in your heart, don’t go – because it is love that is needed to heal this community.’

He asks us to search our hearts, and if we feel ready, to come forward and stand before the congregation. I look into my heart. First I find my fear –of what could happen in the demonstrations, and even more, what could happen in jail. I face my fear and walk through the worst case scenario. Then I find my anger. Letting go of my outrage is a more difficult challenge. How do we forgive so much violence? How do we say “no” to the acts of violence and still have compassion for the fear and ignorance of the violator? How do we refrain from violence when people we love are being hurt? How can he ask us to put all this fear and rage aside? I rebel. It isn’t fair.

Yet even with all my resistance I know in the depths of my being that he speaks the truth. If he lives with discrimination every day of his life and can do this, then surely I can. I wrestle with my angry voice. I pray. I argue with myself some more. I try identifying with the segregationists who are afraid of change. Finally I tire of the struggle and surrender. I relax and feel peace. My heart opens. I rest in the stillness. At last, I open my eyes, take a deep breath, walk to the front of the church, and stand with the others.” Excerpted from “A Tribute to Martin Luther King, Jr.” By Kathryn J. Fentress, Ph.D.

One hundred marched that night – in pairs. Kathryn’s partner was a young black boy. He trembled with fear and she reached out and held his hand. The marchers sang as they entered the white part of town and approached the plaza with its old slave market in the center of town. Facing them was a crowd of white men, women and children, faces distorted with rage, screaming ugly curses at them. National guardsmen with police dogs were there as well, but they do not restrain the mob when they try to rush the marchers. They do not prevent the marchers being hit by flying objects. No one retaliates and we marched back to the church, proud of our courage.

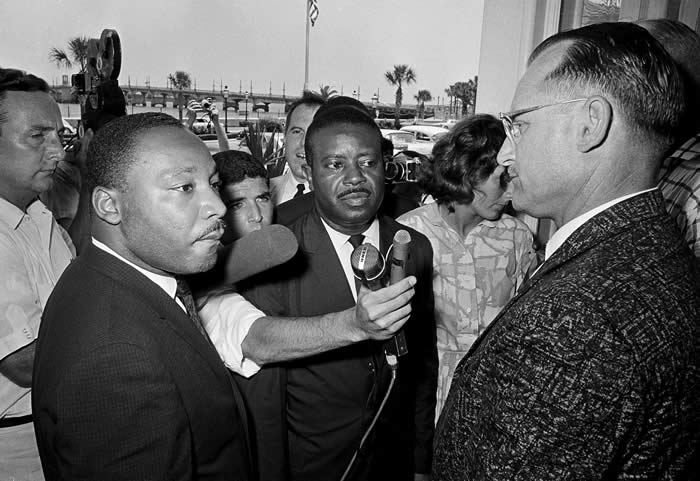

The next day, Kathryn met with Dr. King who asked her if she would be willing to go with him to a sit-in and p robably to jail. She was and did, feeling honored to be asked, and rode with Dr. King and three others to the parking lot of the Monson Motel on San Marco Avenue. They were all arrested before they could even enter the restaurant. Dr. King was taken to the jail in St. Augustine and later moved (for his safety, they said, to the Jacksonville jail. Kathryn and the others went to the St.Johns County jail. Kathryn was charged with intent to breach the peace, conspiracy, and trespassing with malice. The jail was segregated. Kathryn and another white woman demonstrator from the north were put in one cell with two other women, one charged with murder, the other with forgery. The black women were packed into a separate cell, as many as 20 to a cell. It was around the corner, and she could not see the black girls, but they could talk. Of her time in the jail cell, Kathryn said, in an interview with a reporter from the Daytona Beach News Journal, that the Negro girls had workshops in their cells, discussing the philosophy and methods of non-violent resistance, and singing. Food was mostly rice and beans and peanut butter and jelly sandwiches with a great shortage of peanut butter in them. Her mother (a human rights activist and Kathryn’s greatest supporter) brought fruit which she shared with the Negro girls. Although she and the white women in the cell with her were given water and glasses to drink from, the Negro girls had neither. Their protests over the lack of water resulted in their visiting rights being taken away.

robably to jail. She was and did, feeling honored to be asked, and rode with Dr. King and three others to the parking lot of the Monson Motel on San Marco Avenue. They were all arrested before they could even enter the restaurant. Dr. King was taken to the jail in St. Augustine and later moved (for his safety, they said, to the Jacksonville jail. Kathryn and the others went to the St.Johns County jail. Kathryn was charged with intent to breach the peace, conspiracy, and trespassing with malice. The jail was segregated. Kathryn and another white woman demonstrator from the north were put in one cell with two other women, one charged with murder, the other with forgery. The black women were packed into a separate cell, as many as 20 to a cell. It was around the corner, and she could not see the black girls, but they could talk. Of her time in the jail cell, Kathryn said, in an interview with a reporter from the Daytona Beach News Journal, that the Negro girls had workshops in their cells, discussing the philosophy and methods of non-violent resistance, and singing. Food was mostly rice and beans and peanut butter and jelly sandwiches with a great shortage of peanut butter in them. Her mother (a human rights activist and Kathryn’s greatest supporter) brought fruit which she shared with the Negro girls. Although she and the white women in the cell with her were given water and glasses to drink from, the Negro girls had neither. Their protests over the lack of water resulted in their visiting rights being taken away.

SCLC’s plan was to pack the jail in the following days with repeated sit-in attempts, and so Kathryn was surprised after 6 days to find she had been bonded out by SCLC. She was told that a deputy had warned SCLC that they had learned the white women in the cell were planning to “do her in” that night.

Kathryn returned home to Ormond Beach that night, to celebrate her 20th birthday, and promptly returned to St. Augustine and the struggle for justice. Two days after having been bonded out of jail, she was arrested again. She had been asked to drive 4 young black children to the Monson Motel where they were to run from the car and jump into the motel pool. When she pulled up in front of the motel, however, the children were so frightened that they would not get out of the car. Kathryn knew she could not stay there, her car was known, and she coaxed the children to leave, but by the time they did, a policeman was behind her and arrested her for “breach of peace” and “stopping on highway to discharge passengers.” She was taken to the county jail again, but SCLC bonded her out immediately.

Kathryn’s experiences with the law enforcement organizations – city, county and state-caused a deep psychological wound in her personality. They became the enemy. The only place she felt safe was in Lincolnville, the black community of St. Augustine. She felt that she was, at least in some small part, able to identify with the feelings of the residents of Lincolnville that you are in danger the minute you cross the line into the white community. Fear became a daily companion for her, for she knew the police would not help her. She had witnessed them during the nightly marches, holding the leashes of their big dogs in front of them, standing between the white mob with their bricks and bats and ugly words, and the marchers - and they were facing the marchers, not the mob, as if the marchers were the danger.

She was filled with a frightened, sick dread every time she saw a police car in her rear view mirror, or passed a patrol car on the road, or saw a policeman on the sidewalk before her. So deep was the fear conditioning that it followed her for years, and across the country. In later life, Kathryn had moved to Washington State, and had several occasions to drive back to Florida. She found she had to avoid driving across Mississippi or Alabama – it was not safe, her inner psyche told her. Even though she knew that her fear had no foundation in reality all those years later, it was too deeply embedded to be simply rationalized away.

Nevertheless, Kathryn did have two experiences with local police that were somewhat positive, and allowed her to see into the mindset of one man born and reared in the segregated south.

The day she went to jail with Dr. King, she was being processed at the jail when a deputy came over to her. The clearly puzzled look on his face said without words that he could not understand what a young, white woman could be doing mixed up in this scene. He asked her where she worked, and when she responded that she went to college, he asked her where. When she told him Duke University, he was outraged.

“Duke!, “ he said. “I don’t believe that for a minute. My niece goes there. You have to be smart to get in there. You couldn’t possibly be going there.” Although he didn’t say the words, his meaning ‘Someone like you couldn’t be going to Duke’ was clear.

Kathryn understood that what was happening to him at that moment was a total upset of his world view of what was right and normal. A girl going to Duke from the South was prim and proper and a young lady, she could never be involved with anything like the civil rights demonstrations. Kathryn asked him his niece’s name, and it happened that she knew her and which dorm she lived in. When she told him that, his puzzlement was complete. He could not reconcile his lifetime beliefs with the reality of Kathryn’s identity and behavior.

After her second jailing, Kathryn was asked to drive a young white woman who had come up from Miami to demonstrate and needed to go home. She needed a ride to the bus station, which was in the white part of town. As afraid as she was to go into that section of town, she agreed to do it, knowing the young woman would be safer with her than with a black driver. The sight of black and white together in other than the understood “correct” relationships brought out the worst behavior in the white mobs. She drove to the bus station, but once there, the girl would not get out of the car. She was immobilized with fear. Other passengers, black and white, could be seen in the station, and Kathryn tried to assure her that she would be fine in there. “You need to go out and get in the station. It is not safe for us to be here. The police and the Klan know this car,” she told her. The girl would not move, and shortly a white cop came over to the car. He asked what we were doing there - he knew who we were. Kathryn said she was just waiting for the bus, and it should be there any minute. “You can’t stay here. You see that building over there?” The cop said, pointing to a small building beside the bus station. “That’s where the local gun club meets. They meet every week, and they are in there now. It would not be a good idea for them to come out of there and see you girls here.”

Kathryn knew that the “gun club” was actually the local chapter of the Ku Klux Klan. She thanked the cop, and fortunately the bus pulled up at that minute, the Miami girl jumped out and onto the bus, and Kathryn drove out as fast as she could, accepting that this cop, at least, was really trying to be helpful.

Kathryn’s active involvement in the civil rights movement in St. Augustine ended after the summer of 1964. She returned to Duke University, got her degree in psychology, eventually earning her doctorate in psychology. Career, marriage and family claimed her time, but the spiritual journey she began at 17 at Fisk University has been a sojourn of a lifetime. Like many of the 60’s generation of idealists who put their hearts and souls and bodies into the struggle to make the United States a better world, the murders of John and Robert Kennedy, of Dr. King and the killing of the Kent State students made her feel that a ‘deep darkness had settled on the land and it was unsafe to go to the streets again, no matter how noble or just the cause’.

However, Kathryn says, “I basically went underground politically, letting my political activism be expressed through my work, as a psychologist. I try to empower my clients to challenge their programs, their belief systems, helping them to be more compassionate and empathetic.

My work has been undercover for many years, until recently when the widespread, global efforts to end social and economic injustice, and to protect our environment, have made it safe to be an activist again. I still believe, as I did when I was 17, that I need to stand up and participate in these humanitarian causes.

The journey of the spirit is never finished, especially not when the journey is being taken by someone who exemplifies the true meaning of courage. It lies not in the absence of fear, but rather when the fear is intensely present, and the person faces it and does what he or she knows to be right. Such a person is Kathryn Fentress.

Interviewed by Shirley Bryce

The information for this article has come from the following sources:

1. First person interview with Kathryn Fentress on July 1, 2010, in St. Augustine,

Florida. Interviewer: Shirley Bryce, on behalf of ACCORD.

2. “A Tribute to Martin Luther King, Jr.” by Kathryn J. Fentress, Ph.D.

(used with her permission)

3. Articles from the Daytona Beach News Journal of June, 1964

4. Arrest records from the St. Johns County Sheriff’s Office.

Dr. Kathryn Fentress was the Guest Speaker, on July 2, 2010, for the 4th Annual ACCORD Freedom Trail Luncheon presented by the Northrop Grumman Corporation: commemorating the 46th Anniversary of the Signing of the Landmark Civil Rights Act of 1964 and honoring the heroes and sheroes of the Civil Rights Movement of St. Augustine, FL. United States Representative, the Honorable Congressman John R. Lewis was the Keynote Speaker.

— Shirley Bryce

Copyright © 2010, 40th ACCORD, Inc.